A decade ago, I began to tailor watershed education into my children’s environmental program. At the outset, this was spurred by my knowledge of fracking in Pennsylvania and bumping into an impressive National Geographic video, “Why Care About Water.”

The profound words that struck and stuck: “We forget that we live in a hydrosphere and that all of our water resources are connected. Water that runs in the Ganges could also end up in the Hudson, or could fall into the plains of Africa, or could make a cup of tea in the queen’s palace.”

“Less than 2% of the water in the world is fresh and renewable by the water cycle.” These few stark words left me with a mission. Watershed education became a passionate path.

My Penn State training in videography has always been an important thread in my educational efforts. I began to juxtapose the importance of watershed protection into my video education and highlighted fracking accidents that stream poisonous fracking toxins into our fresh water.

Also a decade ago, I saw a glaring lack of watershed education. For me, it was an urgent problem that ran parallel to the climate change crisis and a serious lack of green infrastructure best practices that counter climate change in our Commonwealth.

Not only was this education missing to the public, but also to the governing stewards of our townships and boroughs and cities. Our governing stewards are the path creators of ordinances that would bring those best practices to our communities.

Compounding our work as environmental educators was a climate-denying administration. Watershed and climate education was relegated to the hands of environmental organizations and advocates. Our efforts manifested through Climate March after Climate March.

I always circle back to educating our children, because it is their future we must seriously tend to. I created a workshop that was an outgrowth of a Pennsylvania Association of Environmental Educators conference I attended. A Carnegie Mellon presenter performed a paint tray demonstration about how storms run sediment into the largest body of water when there is an absence of green infrastructure.

I expanded that demonstration to a workshop that fits within the timespan of one class. Students build an entire “green” community in a paint tray lined with electrical tape for the streets. They were given various substrates of sponges for trees and gardens, tiny towels and fabric for green grass, blue sponges for rain barrels, Legos for the buildings. Teams of three were formed with three full water pitchers in front of each team. Perforated Styrofoam cups were placed by each pitcher. They were given 20-25 minutes to create their green community and then there was the shout-out of “EXTREME WEATHER EVENT,” and the flooding began in their towns/watersheds.

Students knew they would ALL flood, but the town with the best green infrastructure would flood the least. The children had to name their community and create a sign for their “Green Town.” At the end of the event, the towns were judged by the students as they walked around the tables of towns and determined who flooded the most and the least. This project was time tick-tock intense.

Finally, students not only performed team skills, but they would possess education they could carry into their adult life. They could run for township supervisor knowing what had to be done to create their best “green” community.

For our early learners, I had an artist put together a flier for event handouts, “How the Water Sheds in your Watershed.”

I then turned to creating a video project, “The Green Connection Documentary – Making a Change for Climate Change for Address Earth. One of my golden nugget interviews was with Frank Niepold, senior climate education program manager at NOAA’s Climate Program Office and Climate.gov. After a year of interviews with the hierarchy of climate and best practices educators, I released my film just as COVID hit.

The documentary leads with the epidemic crisis we face in “worst practices” and ends with the strength of our children’s voices of concern.

A new administration has given rapid rise to all of our work, with grants and a support system.

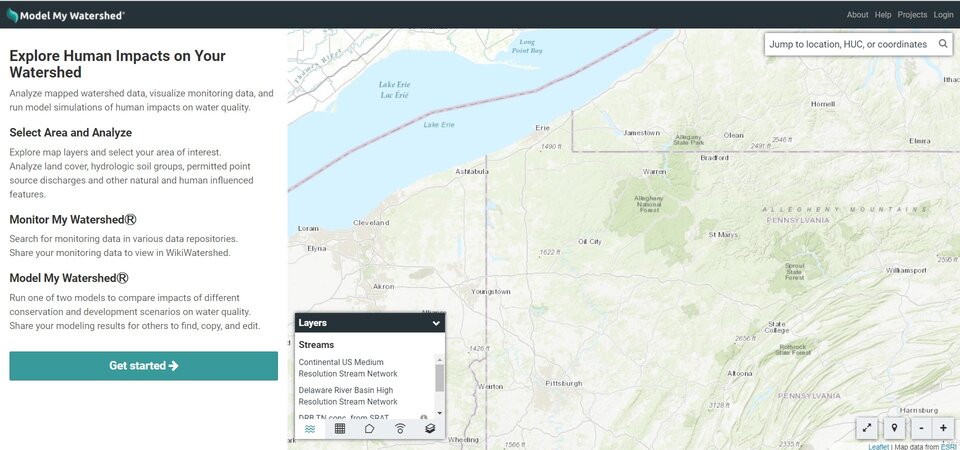

The Pennsylvania Lake Erie Watershed Association (PLEWA), located in Erie, Pennsylvania, is comprised of members of various environmental groups and local governmental agencies, and works on environmental issues in the Lake Erie Watershed. They recently held a Zoom watershed education workshop bringing Stroud Water Research Center’s groundbreaking Model My Watershed app to our watershed working toolbox.

As the watershed representative to Scott’s Run, I was akin to a child with a new toy. However, I found my stream in my watershed was not on the map, so a tool within the app allowed me to draw the area once the location was found. What we had available was Google for latitude and longitude from a physical location.

I found the tool remarkably easily facilitates drawing your boundaries in the “Select Area and Analyze.” With a “Get Started” button, a “Select Area” page opens. Once that page opens you have an option to “free draw” your stream. Drawing the boundaries was as easy as navigating the cursor and clicking on a start point, click the cursor to draw your boundaries. The app facilitates complete ease of navigation. You can explore map layers and select your area of interest. You can be thorough in your data gathering and analyze land cover, hydrologic soil groups, permitted point source discharges, and other natural and human-influenced features.

I put together a small team that included Scott Sjolander (Penn State Extension) and Eric Brown (PLEWA) and began a video reporting of the Scott Run watershed to be done as a “season” effort. The Four Seasons of Scott Run will be a video data documentation of the condition and quality of my watershed. Highlighted by video will be the land and water species, water quality, habitat advantages, etc.

Environmental organizations and educators are finding more and more emphasis on how to protect our watersheds, monitor them, and bring together the data that will tell us the most important element of our work. What is the condition of our fresh water? Are there contaminants endangering citizens and species in that watershed?

Most important in our collective work is how we can best protect the the valuable freshwater sources that flow in our watershed. Because we are one hydrosphere and all water sources are connected.

About the author: Diane Christin Esser is a Penn State Behrend Alumni with a background in film media communication. She is an author, documentary producer, founder of Butterflies for Kids, PLEWA watershed representative, Sierra Club board member, and member of the Pennsylvania Association of Environmental Educators.

We welcome Manage My Watershed members to share their thoughts using the comment form below. Not a member? Register or show your appreciation with the “Like” button. And if you have a watershed story to tell, please share it with our community!

Sarah

I’m so glad you liked ModelMyWatershed. It’s a great tool! And it definitely benefits decision making to think on the watershed level. Thanks for all you do to help educate children and adults!