This story is the second in a two-part series (read part one here) offering a brief overview of stream ecology and monitoring. Though initially written for a fly-fishing audience in southeastern Pennsylvania, the information should be of interest to anyone seeking to be a guardian of their local streams.

People have been using biological monitoring to understand stream impairment since the early 1900s in Europe and since the 1950s in the United States. Quantitative stream monitoring is not as simple as many would like it to be, however.

Many watershed groups go out once in a while and collect macroinvertebrates, do chemistry measurements, and evaluate physical habitat in their local streams, hoping that this will be useful information for characterizing the condition of the stream.

Indeed anybody with the motivation and basic taxonomic knowledge can go to a stream, look under some rocks, or make a couple of net collections and get an idea about its condition. If you go to a stream, turn over a rock, and find a stonefly, then it’s pretty likely that stream is in good condition.

Note that there may be exceptions, e.g., some types of Nemourid stoneflies are naturally conditioned to be tolerant of somewhat acidic conditions, so in cases where moderate acidic pollution is occurring, these types of stoneflies may be found. If you go to another stream and find only midge larvae and worms, that stream is probably not in very good condition.

When federal, state, and county governments evaluate stream and river health, they choose reference sites that represent what they think things should be like in that geographic region and then compare all other streams to this standard. Basically, in the non-arid eastern U.S., it means choosing reference sites that are in forested areas — these are the watersheds that are generally least impacted by human activity. There are certainly exceptions to this — for instance, a single toxic discharge from an abandoned mine in a highly forested watershed can kill everything a stream. Generally, however, if a watershed is highly forested, its streams will likely contain mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies. If the water is cold enough, there will probably be trout.

The problem with amateur stream monitoring is in the repeatability, comparability, and reliability of the data it produces. Assigning an official quantitative rating to a stream based on macroinvertebrate community composition (or any other biological community, e.g., fish and algae) requires using standardized processes involving long lists of supplies, sample processing procedures, taxonomic training, and complicated data analysis and summarization methods.

There are protocols available that are relatively accessible to volunteers, but these still take significant time and effort. Furthermore, the usability of these volunteer-collected data by government agencies can be challenged because of issues in standardization of collection methods, seasonal timing of sampling, taxonomic quality control, sample size and sample processing procedures, geographic calibration issues, and many other factors that can complicate regulatory use.

So what can a person do if they want to make a difference in the health of their local stream? What can one do to help a stream recover from pollution, protect a stream from degradation, or simply understand what the issues and risks are?

What You Can Do to Help Your Local Stream

For an individual who is simply trying to keep track of the condition of their local stream, undertaking an official, technically sound monitoring effort may not be necessary or even possible. Turning over rocks to get a feel for what’s in the stream is certainly a good idea. Many citizen science protocols are available for use in establishing a qualitative (or semi-quantitative) baseline for local stream knowledge.

Paying attention to and identifying the adult insects emerging from the stream can also key an you into what’s living in the stream and in what quantities. And of course, at some point, doing chemistry measurements can be informative, especially if there are suspected pollutants or sources towards which one’s monitoring efforts can be focused.

However, getting out of the water and paying attention to the landscape, the entire watershed, simply walking upstream might be the most important steps that you can take to develop a more holistic understanding of why the local waterway is the way it is.

Look for Stressors

Human disturbance in one form or another is the primary reason that trout do not live in most small to medium-sized streams in southeastern Pennsylvania. Larger rivers in our region are, for the most part, naturally devoid of trout because of warmer water and other physical and chemical characteristics. (To delve deeper into natural longitudinal river progression, read up on the River Continuum Concept.)

The more stressor sources there are (roads and bridges, housing developments, agriculture, industrial effluents, illicit and accidental discharges and spills, etc.), the less likely it is that streams draining the watershed can support a healthy community of organisms, including trout and the many foundational microbial, algal, plant, and macroinvertebrate species on which they rely.

Keep an Eye on Land Use

Knowing what has happened on the land historically, what the current issues are, and what future risks there may be is critical knowledge that can empower action. Proactive citizens who understand the risks associated with these problems can be powerful influences on local management and decision-making in support of local water resources.

Those who want to make a difference in their watershed should engage in the planning process and join watershed protection efforts.

In this effort they should consider asking questions like, “Is this the best we can do?” and “Will this action protect what we have?” You may not get an answer but it’s important to pose the questions for decision-makers to reflect upon and consider.

Understanding Fishery Management

In the context of trout fishery management, anglers need to realize that being able to catch fish in a stream does not necessarily mean anything about the stream’s health. In fact, in southeastern Pennsylvania, some streams support reproducing trout populations despite high levels of human activity and associated stressors (e.g., Valley Creek, Little Valley Creek, West Valley Creek). As described in Part One of this article, these resilient streams are usually limestone spring creeks that stay cold all year long. High natural alkalinity can buffer some of the toxicity originating from the surrounding anthropogenic land uses. Even in these situations where wild trout populations persist, reproduction usually declines, fish size gets smaller, and stocking is often used to increase numbers.

Furthermore, the macroinvertebrate communities in these streams are often degraded, and overall conditions are rated as “fair” or “poor” according to regulatory standards. In many other cases without limestone buffering, streams are even more degraded, trout reproduction has stopped entirely, and regular stocking is the only reason trout are found.

Because of the decline in trout populations, we have developed ways to keep them in the streams to hold on to our love of trout fishing. The primary way being, as mentioned above, the stocking of hatchery-raised fish – breeding and rearing trout somewhere else, where water is cold and clean, and then transporting these fish to other streams that are no longer able to support populations on their own.

Stocking is how brown trout and rainbow trout made their way to the eastern U.S. long ago and continues to be why these species are found in many of our local streams. In addition to being more resistant to toxic and thermal pollution, browns and rainbows compete with brook trout for limited food, habitat, and spawning resources. In fact, many conservation and environmental groups consider brown and rainbow trout to be invasive species in the eastern U.S. Ironically, brook trout have been stocked in western U.S. streams and rivers where they have pushed out indigenous species such as the cutthroat trout.

Even more ironic still, many of the spring creeks and forested streams on which hatcheries are located end up suffering from diseases, nutrients, and other wastes produced by the hatcheries.

If you’re an angler interested in going beyond catching fish and want to build your understanding of the ecology of watersheds and support the health of your local stream, here are some things that you can do.

Are the trout you’re catching stocked or stream-bred? Stocked fish may have missing or worn fins, washed out and faded colors, and if recently stocked, may be found at isolated points in the stream where the stocking occurred.

If the trout are stocked, consider these questions:

- Are they stocked because there is no natural reproduction in the stream?

- If there is natural reproduction, but stocking is still occurring, is it necessary?

- If the stream were left alone, would the wild population become more robust without the competition from the stocked fish?

- What could be done to improve conditions to support natural reproduction?

- Is the water cold enough in the summer?

- What are fisheries managers doing in terms of catch and size limits, and could alterations to these regulations better support a wild or native trout fishery?

Understand what types of macroinvertebrates are found in high-quality streams and what ones are found in low-quality streams — compare this to what you see in your local fishery. Look under the rocks and catch bugs flying in the air, then use a good taxonomic reference to help with identification (e.g., for larvae, Macroinvertebrates.org; for adults, Hatches II: A Complete Guide to the Hatches of North American Trout Streams by Caucci and Nastasi).

If you want to go the extra step, find a local watershed group to partner with on macroinvertebrate sampling and other types of stream monitoring.

Pay attention to water temperature — any stream regularly above 70° F will be questionable as to whether it can support any trout species. Connect this to the landscape and think about how much of the stream along its course is currently shaded. If your stream of interest stays cold, think about how things like reduced shade from cutting streamside trees and warm stormwater runoff from asphalt associated with potential future developments could affect the trout population. If your stream is warm and has minimal riparian tree cover, consider whether there are significant unshaded sections where streamside tree cover could be restored to reduce water temperature.

What’s Stressing Your Stream?

- How close are the roads in your watershed to the streams? How many bridge crossings are there? How many housing developments, construction areas, stores, and industrial areas are within 100 feet of your streams?

- Are there vegetated buffers, trees, shrubs, and other vegetation between the stream and human activity? Riparian (streamside) buffers do just that — they buffer pollution — any stream that does not have a buffer is at a much higher risk of pollution from whatever contaminants are associated with the adjacent land use.

- Are there culverts and dams in your watershed? If yes, are trout and other fish able to pass through these sections, or do the structures block their movement? Habitat fragmentation has significant effects on trout populations, fish size, and spawning success. Trout Unlimited has made a lot of progress in recent years in redesigning culverts to reduce habitat fragmentation and support whole-system connectivity.

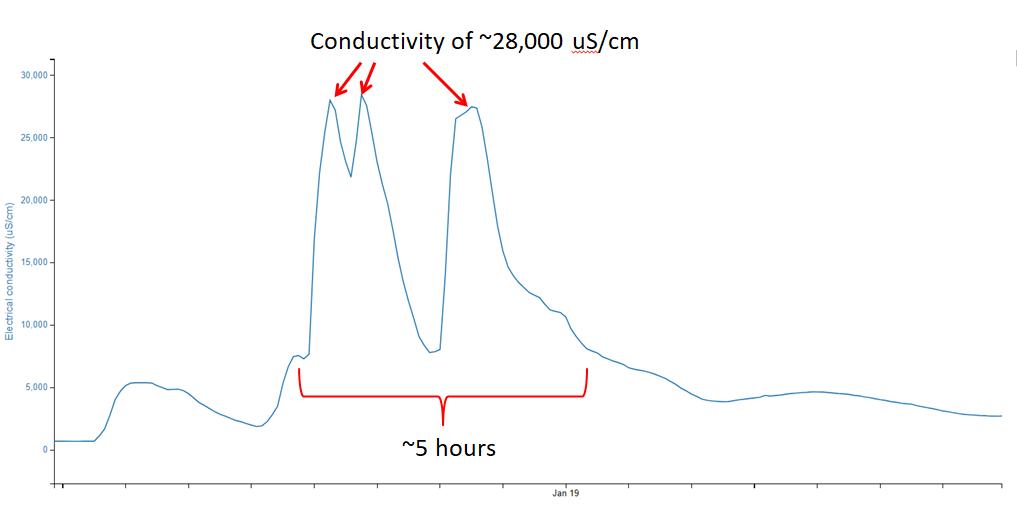

- Go out in a winter storm and see how much salt is on roads and parking lots; watch where the melting ice and snow goes. If it disappears into a storm drain, figure out where that storm drain goes – most likely, it goes directly into a nearby stream. With more development, more road salt is being applied. Salt is accumulating in the soil and groundwater, causing the salinization of streams and rivers across the country.

- Go out in a rainstorm and see where the water goes. Does the water slowly infiltrate into the ground or quickly run over the top of the land, across pavement, farm fields, lawns, and into the nearest stream channel or storm drain? What does this water flowing over the top of the land gather in its path to the stream? Consider how a lot of water running quickly and powerfully from the land to the stream may affect stream banks, stream substrate and habitat, water levels, and flooding downstream.

Those who want to go deeper into how data are used in relation to regulations and management can investigate local data, look up completed studies, use websites that have ranked streams and fisheries, and build an understanding of how regulations function. Here are a few resources in Pennsylvania:

- Maps and lists of trout-supporting waters in Pennsylvania

- Interactive map of Pennsylvania aquatic, recreational, and drinking water use

- Impaired Waters of Chester County

- Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection’s Water Quality site

- Penn Future’s Stream Redesignation Handbook

For federal regulations, research the Clean Water Act and the function of its sections on Designated Uses (aquatic life/recreation/drinking water) and Water Quality Standards. Good places to start are the EPA’s Introduction to the Clean Water Act and the Wikipedia entry.

Call to Action

- Pay attention to what’s happening in your watershed. Get involved proactively and support others who are working on the issues. But don’t be afraid to become an authority and make things happen yourself (long-term local knowledge is invaluable, and standing up for your home water can be a powerful influence).

- If your stream is healthy, keep tabs on how land use may change in the future. Make an effort to understand who is making the decisions in your locality and figure out how you can influence the decision-making process when risky activity is being planned or considered. Valley Forge Trout Unlimited is good at this and has been doing it for over 40 years.

- If your stream is degraded and you want it to improve, try to understand why it is the way it is. Is there a specific isolated issue? Is the water simply too warm and needs more shade to support trout? Or is it a pervasive problem caused by many stressors and sources? Either way, look into what work is being done to improve the situation and figure out what personal skills and knowledge you have that can support the effort. If nothing is being done in your watershed and you know action needs to be taken, find examples that can help focus your efforts and make something happen.

- Get involved with a local environmental action committee (EAC) to support/influence municipal and county decision-making (or even start an EAC on your own). Your county’s Penn State Master Watershed Stewards organization may be able to help direct your efforts.

- Anglers, use your insights to inform, assist, and guide the work of local watershed groups. Many fly anglers are on the water far more than many aquatic ecologists and often understand the stream in subtle ways not observed by the scientists.

If you haven’t already done so, consider transitioning your love and understanding of your local stream to a more comprehensive understanding and love of the watershed as a whole.

About the author: Dave Bressler is the citizen science project coordinator at Stroud Water Research Center, which seeks to advance knowledge and stewardship of freshwater systems through global research, education, and watershed restoration. Dave grew up in central Pennsylvania and started fly fishing in his early teens on the Little Juniata, Spruce Creek, and Spring Creek. Since then he has tied flies and fished them on streams and rivers in most parts of the country that have trout.

We welcome Manage My Watershed members to share their thoughts using the comment form below. Not a member? Register or show your appreciation with the “Like” button. And if you have a watershed story to tell, please share it with our community!